A Little Background

The dollar we know was first seen in 1929, replacing considerably larger, and harder to handle bills.

Today’s dollar bill measures 2.61″ wide and 6.14″ long. These odd dimensions seem arbitrary and random, but there was a very good reason for them – given the size of the paper sheets on which they were printed at the time, these dimensions used the whole sheet with little or no waste.

Our paper money is not paper at all; it is 75% cotton and 25% linen. So indeed, our paper money is actually cloth money, which is why it is not destroyed when it goes through the laundry.

It costs about 4.1 cents to create one one-dollar bill. For perspective, it costs

- 3.1 – 3.7 cents to produce a penny (discontinued in 2025)

- 11.5 – 13.8 cents to produce a nickel

- 5.3 – 5.8 cents to produce a dime

- 11.6 – 14.7 cents to produce a quarter

The $1 bill accounts for 31% of all the currency the US produces. The government prints about 38 million one dollar bills a day. There are over 14 billion one-dollar bills in circulation today.

The average lifespan of a $1 bill is around 6-1/2 years.

Every $1 Bill is Unique

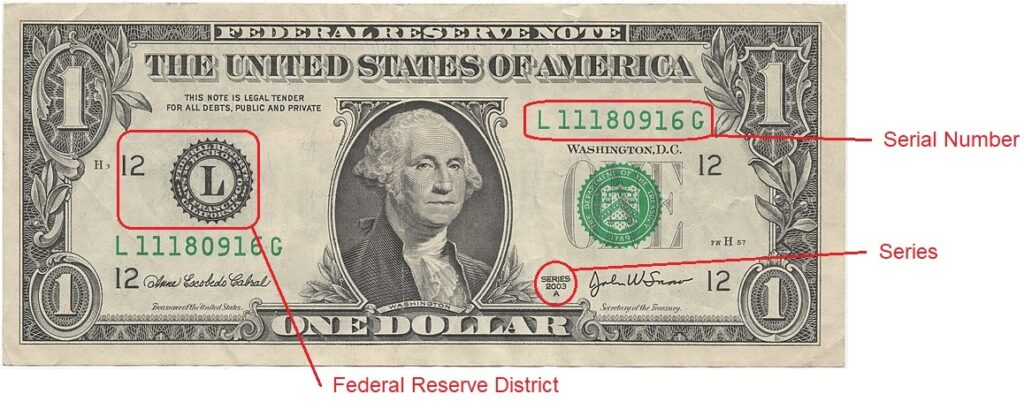

According to published government records, by December 31, 2025 there were about 16 billion one-dollar bills in circulation, and every one of them is unique. What makes them unique is the combination of series, federal reserve district, and serial number.

The SERIES indicates the year the current design was approved.

The FEDERAL RESERVE DISTRICT letter and number represent the federal reserve district to which the bill was assigned.

The SERIAL NUMBER counts how many bills were produced within a given SERIES for a given FEDERAL RESERVE DISTRICT.

When the SERIES or FEDERAL RESERVE DISTRICT changes, the SERIAL NUMBER resets to zero.

The series is not necessarily the year the bill was produced but represents the approval of a new design of the bill. The series changes when new signatures are placed on the bill. When a letter is present in the series, it indicates that a minor change has been made, usually not a visible change, but perhaps the type of ink or type of printing process.

There are twelve federal reserve districts, each represented by a number and corresponding letter, such as 1 and A, 2 and B, …, 12 and L.

The 12 Federal Reserve districts are:

- A-1 Boston

- B-2 New York

- C-3 Philadelphia

- D-4 Cleveland

- E-5 Richmond

- F-6 Atlanta

- G-7 Chicago

- H-8 St. Louis

- I-9 Minneapolis

- J-10 Kansas City

- K-11 Dallas

- L-12 San Francisco

About the Serial Number

For $1 and $2 bills, the serial number consists of one letter, eight digits, and one letter.

The prefix letter corresponds with the federal reserve district.

The eight digits run from 00000001 to 99200000. There is a fascinating history behind why the limit is 99200000, but it will not be shared here.

For the convenience of discussion, eight digits can represent 100,000,000 (one hundred million) numbers from 00000000 to 99999999.

When the one hundred million numbers have been exhausted, the suffix letter, which starts with A, increments. Of twenty-six letters, the letter O and Z are excluded from the series. That means the one hundred million numbers can be repeated up to twenty-four times. Therefore, 2,400,000,000 (two billion, four hundred million) distinct numbers can be represented. The example shown above tells you that the number 11180916 has been used at least seven times, G being the seventh letter of the alphabet, within the series 2003 A and the San Francisco federal reserve district, district 12, also represented as L.

So that means that the number 11180916 appears on at least six other 2003 A, San Francisco dollar bills out in the wild.

And, statistically, the number 11180916 will appear on one or more dollar bills in series 2003 A in the other eleven federal reserve districts, and likely many more times as the suffix letter increase through twenty-four letters.

Since the year 2000, there have been 9 series of one-dollar bills (2001, 2003, 2003A, 2006, 2009, 2013, 2017, 2017A, and 2021). Each time the series changes, the serial number resets to the beginning.

The New Hobby

It is my new hobby to find duplicates of serial numbers, limited to the eight digits.

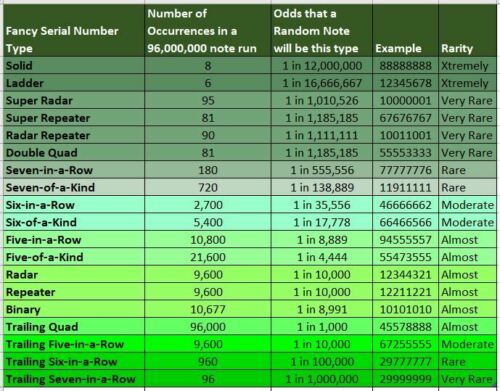

At the same time, I will be seeking ‘fancy’ serial numbers. A fancy serial number has many forms: eight consecutive digits in order (01234567); all eight digits the same (22222222); limited to two digits (66776766); repeating patterns (12341234); radar patterns (12344321); 4, 5, 6, or 7 digits in a row (25555550); dates (07041776 – July 4, 1776, 20010911 – September 11, 2001); and many, many others.

The challenge is formidable. In order to find duplicates means you have to have the two bills in hand, which means having thousands, more like tens of thousands bills on hand in order to match the duplicates.

THE CHALLENGES: Tens of thousands of dollars of investment; having a place to store all of them; keeping them in numeric order based on the eight digits only. And, as you may have noticed for yourself, currency changes hands hundreds, thousands, even tens of thousands of times, and quite frankly, are filthy. For reasons of cleanliness and convenience the bills need to be cleaned as they are introduced to the collection. After the bills have been cleaned, they will not lay flat, so each requires a couple of passes with a clothes iron. The bills in general circulation now are predominantly 2021, 2017, and 2017A, so only three resets of the serial numbers. The odds of finding the same eight-digit number on more than one bill is calculated by 1) three series changes times 2) twelve federal reserve districts times 3) however many times the suffix letter changes (I have a 2017 showing a U suffix), against the estimated 16 billion bills in circulation.

THE REWARDS: Being able to find a match. Depending on the condition of the bills, the duplicates can be worth $400 – $500, hardly worth the tens of thousands of dollars put into the search. I am not doing this for the money, even if I should find one of the holy grails of fancy numbers; I am doing this for the challenge and satisfaction.

THE RAW MATERIALS: Once a week my bank sorts through their cash on hand, bundles up the excess bills and sends them back to the federal reserve district bank. I have made arrangements to purchase their excess one dollar bills they would otherwise be sending away. There are three branches of my bank within convenient driving distance. They cannot guarantee they will have excess bills for me to buy each week, but my first week’s buy was $1,450.

THE QUESTION: How much money, time, and space will I devote to the project before I acknowledge that the statistics are against me, terribly against me. Just say I have $25,000 in one-dollar bills cleaned, ironed, sorted, and stored when I decide to give up. I would always wonder if the one-dollar bill I touch next would have been the match I was looking for.

Finds So Far

(xx.x) represents the 'coolness index'

x.xxx% is the percent of 8-digit numbers having this trait

66776776 (99.2)

1) 2 four of a kind, 0.0032%

2) two unique digits, 0.011%

3) three pairs together, 0.075%

38888899 (99.0)

1) 5 of a kind + 1 pair, 0.0052%

60522222 (98.1)

1) 5 of a kind together, 0.037%

08787873 (91.2)

1) 2 triples (7s and 8s), 1.8%

31247650 (97.3)

1) 8 consecutive digits, 0.12%

2) 8 unique digits, 1.8%

19500529

May 5, 1950

09101931

September 10, 1931